- Home

- Enquiries

- Fast Facts

- About Us

- Welcome From Wayne

- Our Discoveries on Kokoda

- About Kokoda Spirit

- Why Trek With Kokoda Spirit

- Kokoda Spirit Staff, Guides, Porters and Carriers

- Our Australian & PNG Team

- Our Australian Guides

- Our PNG Guides

- Our Porters

- Our Partners In Adventure

- Our Booking Terms & Conditions

- Inclusions and Exclusions LOCAL LED 2024

- Inclusions and Exclusions AUS LED 2024

- Trek Dates & Prices

- Our Treks

- Why Choose An Australian Led Kokoda Trail Trek?

- Why Choose A PNG Led Trek ?

- Is There An Easier Direction To Trek Kokoda?

- Kokoda Treks

- Fast Treks

- Kokoda Back To Back

- Kokoda Coast To Coast

- Kokoda Ultra Marathon

- Sandakan Memorial Track

- Sandakan Memorial Trek I Mt Kinabalu Climb

- Everest Base Camp Ultimate Adventure Trek (Includes Helicopter Flights)

- Everest Base Camp Ultimate Trek

- ANZAC Day Hellfire Pass

- Port Moresby – Kokoda and Northern Beaches Tour. Non trekking tour

- Port Moresby Island Getaway

- Beach Heads Tour Buna to Gona 2 Nights / 3 Days

- 3 Night / 4 Day Beach Heads Tour Buna To Gona

- Corporate, Executives & Athletes

- Charity Fundraising Adventure Treks

- School and Youth Leadership Programs

- Testimonials

- Gallery

- Trek Info

Our Discoveries on Kokoda

Japanese Kokoda Veteran First Class Private Minoru Inoue

Overview by Kokoda Spirit owner Wayne Wetherall

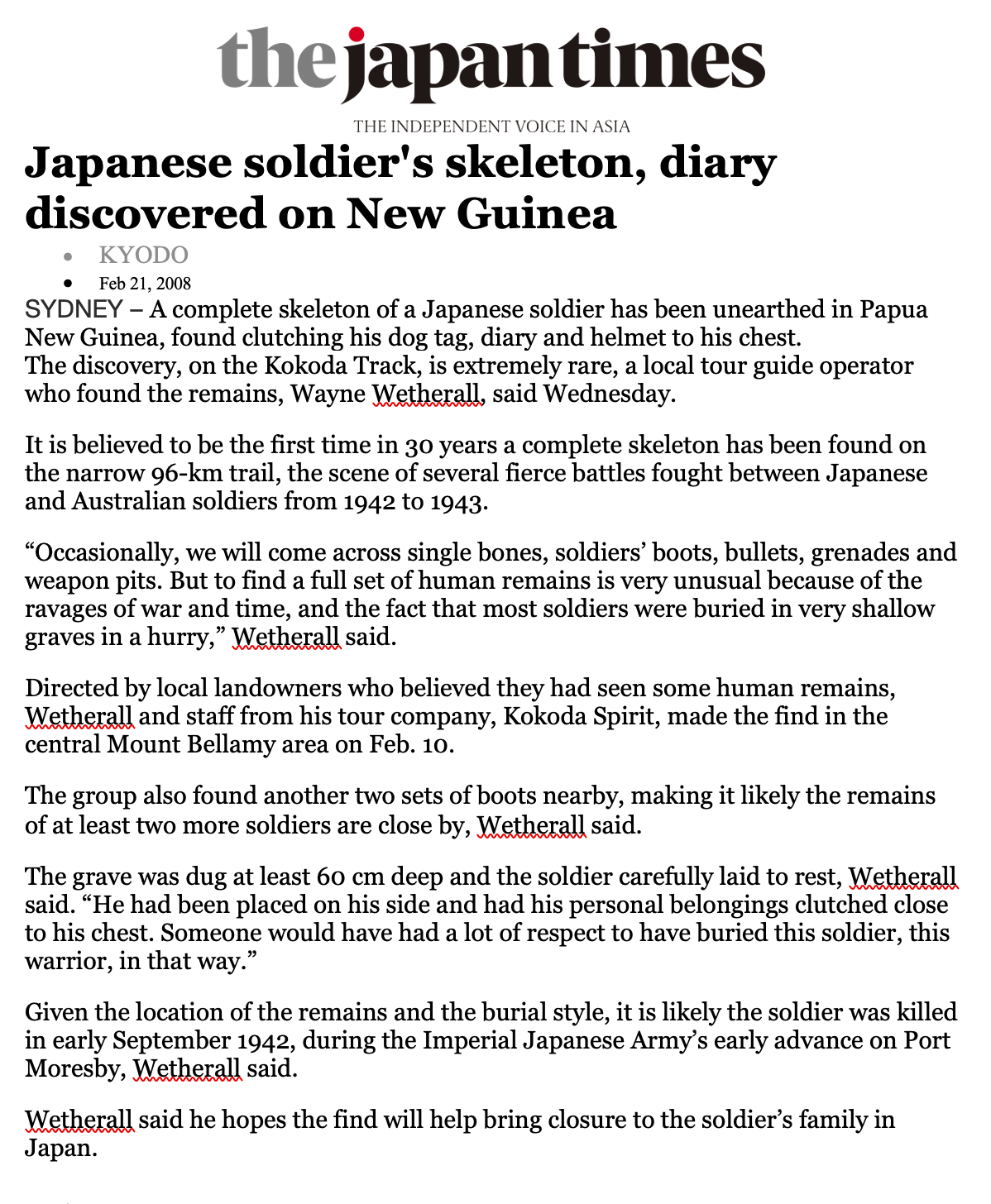

In February 2008 I was on a preseason training trek with my Kokoda Spirit Trek Masters across Kokoda. We had stopped for the night at the 1900 camp site at Mt Bellamy.

The Land Owner ushered us over to the side of the river bank to show us a bone sticking out of the embankment…

Overview by Kokoda Spirit owner Wayne Wetherall

In February 2008 I was on a preseason training trek with my Kokoda Spirit Trek Masters across Kokoda. We had stopped for the night at the 1900 camp site at Mt Bellamy. The Land Owner ushered us over to the side of the river bank to show us a bone sticking out of the embankment.

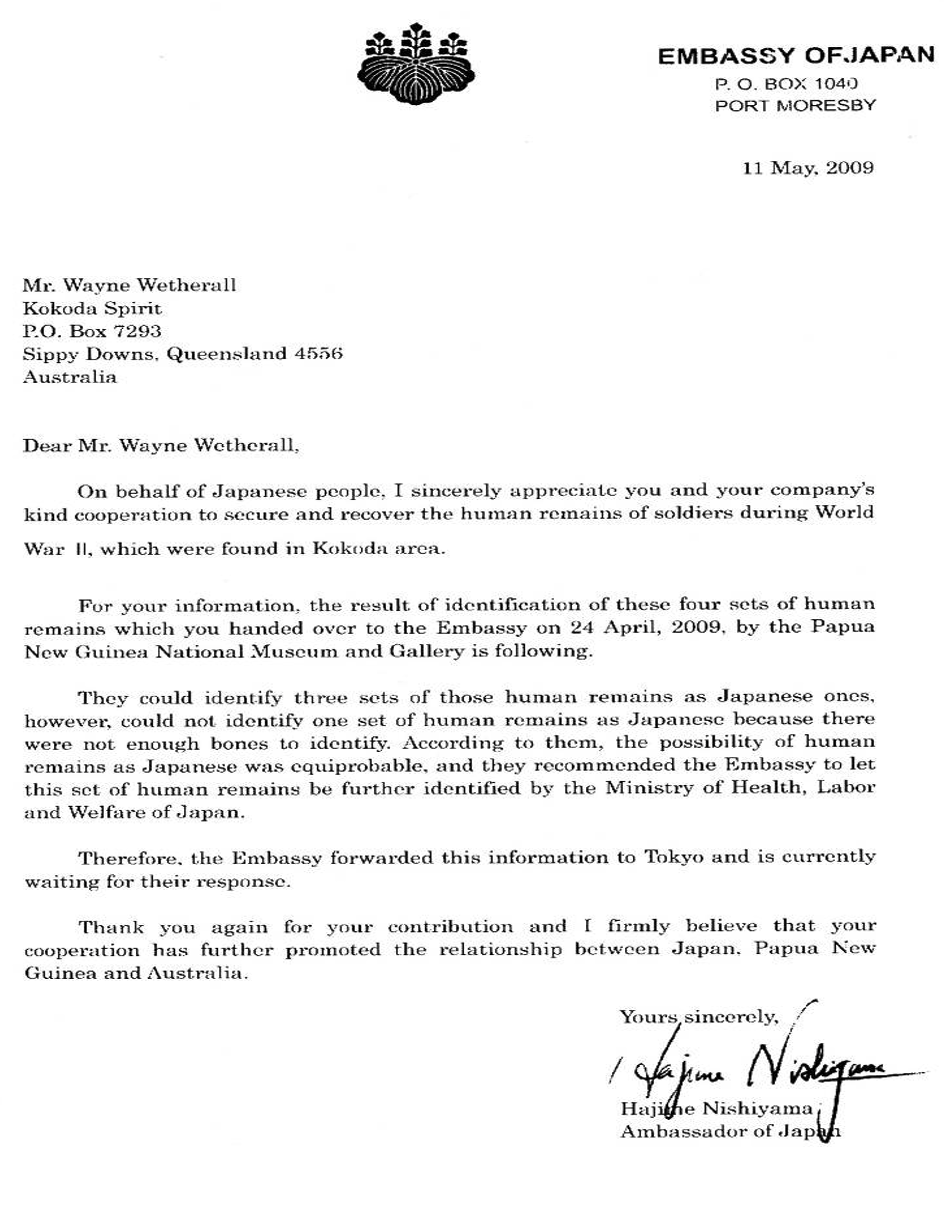

Over a period of many months the relevant authorities including the PNG Museum were consulted along with both the Japanese Embassy and Australian High Commission. The PNG Museum team identified the bones as being Japanese. With the permission and support of the relevant PNG Authorities, Land Owners and the Japanese Embassy we began to recover the remains of the Japanese Soldiers. What we had discovered were the complete graves of four Japanese Soldiers from the 15th Independent Engineers Company. This was the same Regiment of men that were part of the original Japanese landing at Gona on 21 July 1942. They had been buried by the Japanese comrades; their graves dug deeply, four abreast with the remains buried reverently with their arms placed across their chests and their personal effects placed on their chest. This was the first time in over 40 years that the complete skeletal remains of Japanese soldiers had been found on the track.

Usually the soldiers were buried quickly during the battle with a simple service and a ribbon or other identifier on the grave, these identifiers would allow the bodies to be recovered and repatriated back to Japan for proper burial in the Japanese War Cemetery in Tokyo or in their own family plot. Over the years these battlefield war graves were ravished by wild pigs and other wild creatures on the track. Even Nishimura the “Bone Man” of Kokoda found only the remains of the skulls and bottom leg bones of the soldiers.

On the 24th April 2009, I returned the recovered remains of the four Japanese soldiers to the Japanese Ambassador to PNG. This was a simple service carried out at the Gateway Hotel in Port Moresby. Members of my recovery team handed over the boxes of remains.

I was also recently in Japan to hand over the personal effects to the family of one of these four dead Japanese Soldiers. One of the personal effects found on one soldier was a stainless steel cigarette case belonging to Minoru Inoue. I met and presented the cigarette case to Inoue’s younger sister Kitaoka. The meeting was held in the Kitaoka family home and was attended by both the Japanese print and TV media. It was quite a story in Japan about the return of the soldier’s remains and personal effects recovered by an Australia, the former enemy of the Japanese. Another of the soldiers has been identified as Murakam from Osaka.

In March 2010 we had official confirmation that the DNA test undertaken on the remains of Inoue and his younger living brother were a match.

This news was received with great happiness by all concerned, it would now allow for Inoue’s remains to be buried in the family cemetery with a traditional Buddhist ceremony.

With my efforts to return the Japanese remains back to their families in Japan, I was contacted by Japanese Veterans association in Japan, who were grateful for my efforts.

During our original diggings and investigations we became aware of the graves of four more Japanese Soldiers buried in the same area we reported these discoveries back to the relevant authorities

The Japanese Veterans Association along with the Japanese Embassy and The PNG Museum engaged us to recover the remains of these four soldiers which we did and were returned to the Japanese Embassy in Port Moresby. These remains were then returned to Japan.

These same Japanese Veterans association gave me access to their association records, private diaries and maps. It was access to these records and the eyewitness account of Corporal Kokichi Nishimura that gave the major breakthrough in the search for Captain Templeton. I have shared the journey and information regarding the life of one of the Japanese soldiers as the discovery of his remains was the catalyst and impetus for our solving the mystery of Captain Sam Templeton.

First Class Private Minoru Inoue

15th Independent Company, South Seas Detachment

First Class Private Minoru Inoue lent against the 44 Gallon drums stored in the compound of the Giruwa Engineers base near Buna. He tapped open his stainless steel cigarette case and flicked out a hand rolled thin cigar that he had brought for the occasion. He offered his good friend Murakam one of his cigars and they both inhaled deeply the strong spicy smoke. Today, 27th July 1942, was his 21st birthday and the 1st anniversary of his enlistment in the Japanese Army. It was good to have Murakam here with him; he was a good friend and a great engineer. Murakam possessed a beautiful opera singing voice and would often entertain Minoru and the other engineers with modern and traditional Japanese songs.

Minoru had enlisted early in the Engineers Company and had met Murakam during the enrolment process, they both had the dream to build roads and bridges and design new machines to help the Japanese overcome the crippling oil and technology embargo that the Americans had placed on their country. The both of them would often talk late into the night about their designs and ideas. They had planned when the war was over to build their own engineering company and design and build great machines. One section of their business would specialise in infrastructure such as bridges, viaducts and water systems and the other factory would be primarily to research and develop new technology. He felt proud and relieved that so far he had done his job well. His promotion to First Class Private was proof that he was worthy to serve the Emperor as an engineer in the war.

The cigarette case was a going away present from his younger sister Kitaoka. She had saved hard working in her Uncles lacquer ware shop to give her brother the gift and had his name specially engraved into the case. His sister was very sad that her brother was leaving to fight overseas; she was going to miss him greatly. Minoru, reassured his sister that he was an engineer and was not there to fight but to assist the troops with bridges and roads to make their journey across the Owen Stanley’s easier, he would be safe and he would come home just as soon as the job was done.

Minoru smiled to himself as he remembered all the fun times he and his sister had playing with their other brother and sister at home in Kyoto. Kitaoka was Minoru’s favourite sister, even though he was older than his younger sister, she always looked after him. Minoru was very small for his age, even for a Japanese only standing 4ft and 10 inches high, his sister would make sure he was always OK and took great pride in defending her brother against the street boys that teased Minoru around Kyoto.

Minoru remembered one very embarrassing moment when Kitaoka was only 11. Minoru had been sent on an errand and on his return he had run into trouble. She had come to her brother’s aid as he was being roughed up by the Kyoto street boys; she had grabbed a broom from one of the local shopkeepers and started swinging it wildly at the boys. The street boys were so bemused by Kitaokas’ antics that they walked off in fits of laughter.

Minoru’s, father was a traditional Japanese, he was head of the family and his word was to be obeyed. He loved all his children and worked hard to support them and to ensure that they all had a good future. Minoru was his favourite child, perhaps it was because his son had been so sick when he was young and had not been expected to live long or just that he felt more protective towards his smallest son. For whatever his father’s reason for his favoritism he was determined to instilled in Minoru the legends and traditions of their forefathers. His father taught him about the spirit of Bushido, the way of the Samurai. Minoru studied hard and trained in Judo and other Martial arts daily to train his mind and body in the way his father had prescribed. The Bushido Code required complete obedience, loyalty, faithfulness, do what they believe to be correct, courage, courtesy and modesty to live simply.

Even with his intense Bushido training program Minoru only received an average pass on his medical examination for the Army. The Japanese Army had five levels of medical fitness; they were, Very Healthy and Strong, High Distinction, Distinction, Average and Pass. No one failed these medicals, but those with just a pass were only used in absolute emergencies.

The Japanese Army had decided that regardless of academic, professional or other talents everyone from Distinction up would be in the infantry. Minoru never thought too much about his average pass, he just knew it was his destiny; he would not become a foot soldier but a member of Japan’s famous Independent Engineer Companies.

Minoru would write in his diary and described his orders to build a road across the Owen Stanley Ranges as a massive task, but one we are determined to achieve. “We have made great progress initially, our base and logistic depot is now complete and we have commenced our plans for the road across the range.”

The Japanese were so enthused and confident about their plan that they had brought bicycles and horses to ride across the road that they were building; initially it looked like a very achievable plan. The maps supplied to the engineers showed small narrow creeks and rivers, wedged in between some small ranges.

What the engineers and the rest of the Japanese Army soon encountered was raging rivers and steep canyons, their plans of building a road across the Owen Stanley ranges soon ran into trouble.

“We had been supplied by HQ topographical and linear maps of the area; unfortunately these did not correspond to the landscape and terrain that we now faced”

The first major obstacle the soldiers and engineers encountered was a series of steep and spectacular waterfalls at Oivi that rushed down through narrow canyons, blocking the path of the soldiers. The soldiers were forced to climb up through the waterfalls abandoning the pack horses and bicycles.

These waterfalls created the first real challenge for the engineers and that one that needed to be resolved quickly.

The South Seas detachment was on a tight timetable and the steep waterfalls slowed the progress of the supplies and soldiers down. It was important to find a solution to this problem quickly. Minoru and the other engineers surveyed the area and were able to cut a track around the waterfalls, by passing the treacherous climb.

This initial track was subsequently widened and three camp sites over a 1500 m length were established near the water. The Oivi area then became a rest area for the Japanese, providing reliable water and a protected defensive area for their advance across the track and their retreat later in the campaign.

With the new track cut it was then possible for the horses to return to hauling the supplies along the track from Gorari to Oivi, with little difficulty.

Today you can clearly see the track cut by the Japanese from Gorari to Oivi and their camps along the river. On our recent dig in the area we uncovered horse shoes, ammunition, ration tins, bayonets and other remnants from the Japanese camps and battles in this area. It is hard to believe such a beautiful and peaceful place witnessed the passing of so many soldiers and the carnage of battle.

Minoru and his platoon of engineers had made slower progress then expected across the range, being constantly harassed by the Australians and dealing with the terrible conditions and lack of supplies. Their plan to build a road across the track was abandoned at Oivi, the bicycles were discarded and a plan to build a horse and walking track was implemented.

The Japanese engineers soon learned the best and most efficient ways to cut tracks, cross rivers and build ladder and stair systems across the ridges to assist the transportation of men and supplies. Much of the Japanese benching and track building can be seen in parts on the track today. The Japanese had built a series of their own “Golden Stairs”, with thousands and thousands of stairs cut into the ridges across the track and reinforced from timber cut from the jungle. The Japanese, like the Australians soldiers, hated the stairs and both referred to them as stairways to hell. The stairs became more of a hindrance then a help to the soldiers, with them constantly filling with water and mud and breaking under the loads of the soldiers.

In late August and early September the 15th Independent engineers had crossed the highest point of the Owen Stanley ranges. They were camped at over 2000 m in the Moss Forests on MT Bellamy and were feeling the effects of weeks of hard struggle across the range, lack of food, constant rain, fog and the sheer bone rattling cold. Their camp was constantly damp and dark, with the sun struggling to penetrate through the deep forbidding forest.

Masses of giant pandanus trees rise into the jungle, competing for light and nourishment with the giant arctic beech trees that are remnants of a forgotten age. Masses of green maiden hair moss hang from the branches; fluorescent fungi and moss cling to the dead branches and undergrowth. Centipedes and giant ants plough their way through the decaying mulch, oblivious to the constant drizzling, dripping rain. The nights were ablaze with swarms of fire flies, glow worms and the screeching racket of the 6 o clock crickets.

The engineers walked into the Myola Lakes area only being a couple of hours behind the combat soldiers. There they had found a large supply of Australian stores and ammunition. Myola had been the Australians main logistic base on the track, and its abandonment had been a major loss to the Australians but a great bonus for the Japanese.

The Myola area was a large sunken volcano that opened up into vast grass plains high in the mountains. It had been perfect for dropping supplies to the Australian troops. The Australian supplies would then be carried forward by the soldiers or by teams of the Fuzzy Wuzzy Angels.

The discovery of food and supplies in the area by the Japanese was a great relief, as their own rations were very low. The Japanese plan to cross the Owen Stanley ranges in 14 days had taken a severe setback with the aggressive fighting withdrawal tactics implemented by the Australians.

The Australian soldiers had eaten as many of the supplies as they could before burying any left over’s or puncturing cans and smearing blankets with jam. The Japanese had been so desperate for food that many of them ate the spoiled food left by the Australians and became violently and fatally sick.

On the 5th September Minoru and his platoon of engineers moved out of the Moss Forest and trudged on towards Kagi. Their job was to cut and clear the track from the Moss Forest Junction across to Kagi and onto Efogi.

Their mood was buoyant, they were very pleased to be out of the cold dank jungle, the weather was warmer on the other side of the mountain and the sun shone hot and bright. From the Kagi junction they could see the glittering ocean on the outskirts of Moresby. Their comrades in the infantry had done well, the Australians continued to fall back, and soon they would be in Port Moresby.

Take Cover!!

The frantic calls coming from over the peak beyond Kagi signaled the arrival of the deadly allied P-400s and the Australian Wirraway A-20 planes.

Minoru Inoue could hear the drone of the planes approaching, and then the drone became a roar as the planes began their terrifying dive towards the troops. Thousands of Japanese soldiers were on the ridgeline, this was open country, hot and dry and with little natural protection from aerial attack. To be caught out here in the open was to be avoided at all costs.

Wave after wave of planes dived on the columns of men winding the way across the exposed ridgeline in pursuit of the Australians. The pilots knew this area well; it was open and easy to see their targets, scrambling for desperate coverage behind small hills and scrubs. The planes came in low, strafing the Japanese as they cringed and tried to bury their exposed bodies into the hot, red earth.

In between Kagi and Efogi the track drops steeply into the valley making travel difficult and slow, the columns of Japanese troops continued their relentless advance towards the Australians entrenched on Mission Ridge and Brigade Hill. It was difficult terrain to walk on, very slippery and treacherous, to many of the starving Japanese they were walking and fighting like Zombies, surviving somewhere between life and death.

The hardships, punishments and brutality they had endured in training had desensitised them, removing any sense of emotion except the will to fight. Many of the Japanese soldiers had been killed or severely wounded in this section of the track; to the Japanese it became known as Hell Valley.

On the 8th September as the battle for Brigade Hill raged on in to its third day Minoru Inoue and his friend Murakam, started work early on the track north of Kagi. They were widening the track and installing a series of steps into the steep embankments to assist the easy progress of the Soldiers along this section of the track. It was always best to start work here in the early morning before the sun’s intense heat made it unbearable. The Kunai grass in this section of the track radiated the heat dramatically, sending the temperature past 100 degrees by lunch time. The engineers had stuck to their task well, while not suffering the effects of constant battle; they had reach physical exhaustion from the constant physical workload, meager rations and the unrealistic demands of the commanders.

While they worked they kept an ever watchful eye and ear out for allied aircraft, the last allied air attack had occurred two days ago on the 6th September, which resulted in the death and injury of many of the troops.

As they rested on the side of the track they became aware of the drone of aircraft approaching, they were coming from the north of the range through the gap. The devastating attack on the troops two days previously had come from the South, possibly Moresby.

These P-400s and the Wirraway A-20s planes coming from the North could be the own planes or possibly allied planes returning from bombing and strafing raids on the North Coast, so they were not concerned.

The planes continued to fly south high over the heads of the Japanese engineers, apparently oblivious to their presence. Then without warning three of the planes broke from their formation and begun a steep and deliberate dive towards the resting Japanese. The planes came in at just over 100 m high spraying their metal of death onto the fleeing men. It was not unusual for returning allied aircraft to use up any leftover bombs or ammunition on their return from a mission.

When the smoke and dust had cleared three of Minoru’s comrades lay dead, six of them had been wounded including Minoru who had taken an aircraft round through the thigh. His friend Murakam lay severely wounded in the ditch. The remaining engineers worked frantically to help the wounded, stopping the bleeding, adding some supplementary solvents and bandaging the wounds.

The dead engineers were buried that morning on the side of the track, their graves marked for reference, so they could be collected and returned for burial in Japan. The rest of the survivors from the allied air attack including Minoru and Murakam were placed on hurriedly built bush stretches in a desperate bid to get them proper medical aid at the Japanese North Coast Hospital at Giruwa.

The climb back up the ridge was hard; they only made it to the moss forest at the Kagi Gap before they rested for the night. The next morning saw no improvement in the wounded soldier’s health, the stretcher bearers were struggling with lack of food and fatigue, and it was decided to rest for a day near a little river deep inside the Moss Forest. They remembered that there were Australian stores nearby at Myola and a small party set off in search of the desperately needed supplies.

That afternoon Minoru’s great friend Murakam died, they buried him next to the other two dead Engineers on the side of the river bank. Minoru was to sick and weak to weep for his friend, his condition had become critical, there was no hope for him, soon his spirit and soul would be scattered to the wind.

First Class Private Minoru Inoue died that morning, September 10 1942. He was buried next to his comrades and friend Murakam. His body was lowered into the deep cold earth. His arms folded across his chest, his personal items laid with him, including his stainless steel cigarette, watch and compass. His suffering had ended, he had done his job well he had brought great pride to himself, his family, his country and his Emperor.

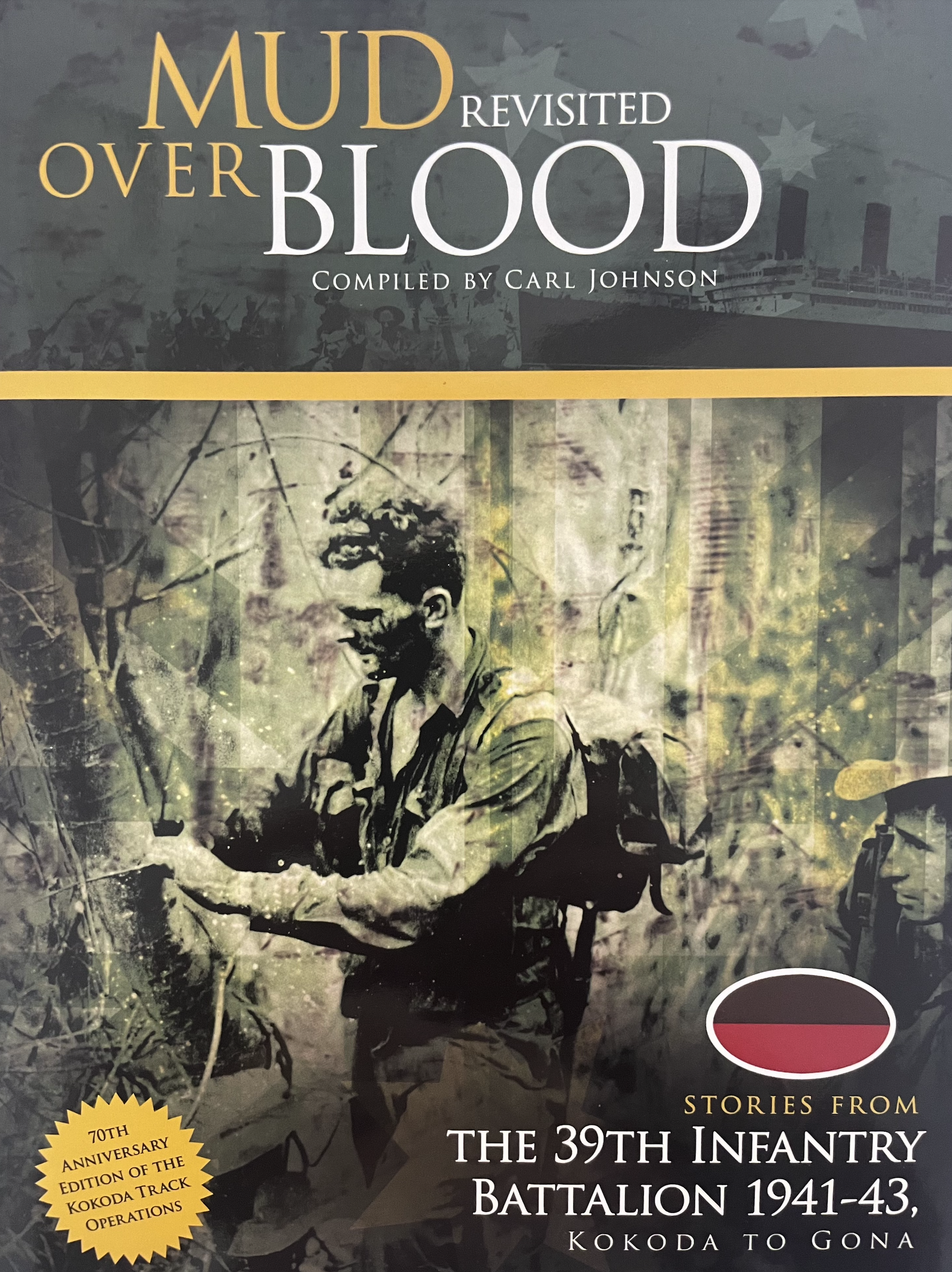

39th Battalion ``Heroes To The End``

Stories from the 39th Infantry Battalion 1941-43

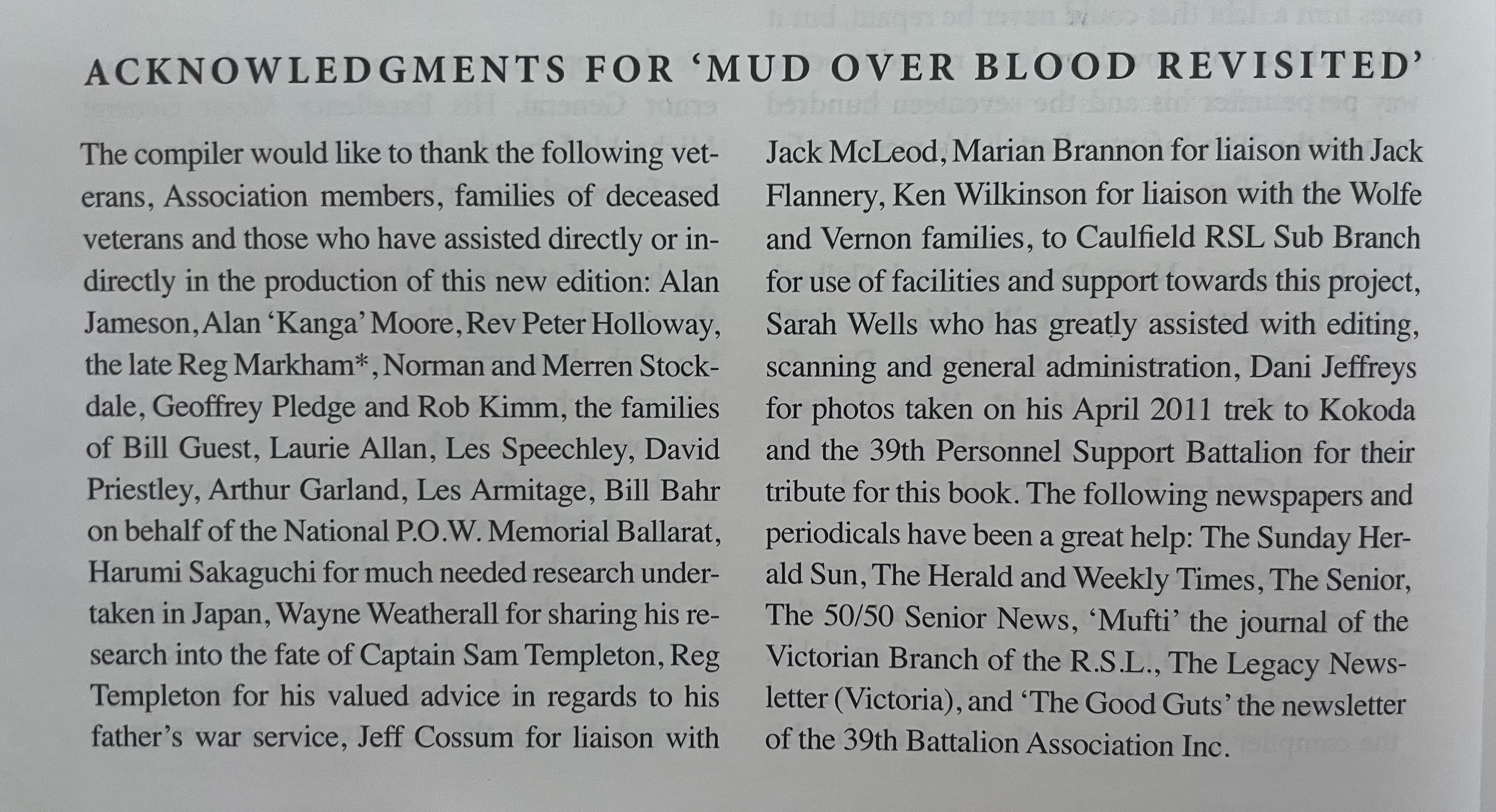

Compiled by Carl Johnson – Mud over Blood & Mud over Blood ‘Revisited’

A brief in regards the final fate of Captain Samuel Templeton and the six other ranks captured between 26-29th July 1942 and executed at Oivi on the Kokoda Trail 15th August 1942.

In 2006 when the 1st edition of ‘Mud Over Blood’ was released, this being primarily a memorial publication intended for those living veterans of the 39th and for the many families of those that had since departed, I chose to query, what till then, had been avoided, the final fate of Captain Templeton on the Kokoda Trail.

‘What Happened to Uncle Sam?’ was intended to put forth as much accurate information, which was till then available both publicly and privately to this compiler. This work was produced prior to the centralisation of ADF records (and digitalisation), which were at the time of collating not then publicly available, and with the assistance of as many of those actual Kokoda Trail veterans involved at these two actions – & who had chosen at that time to speak.

The piece made it very clear that not only was Templeton a known P.O.W. on the Kokoda Trail but so were another six members of the famed 39th Battalion, these being cited on Templeton’s dossier, and having been accounted for by members of ‘B’ and ‘D’ Company who had been present. The compiler made it clear what as well the end fate of these prisoners was to be.

In 2010 a media storm erupted over new revelations by Kokoda Trail Trekking operator and researcher, Mr Wayne Wetherall, who had been advised and shown the actual spot where Templeton had been buried by a Japanese veteran member. The details as then aired by Wayne Wetherall were based on these firsthand accounts, the ability which this veteran demonstrated in being able to accurately place the spot of burial, and an in-depth investigation vide Australian Official records regards the death of this officer by Wayne Wetherall personally.

This compiler was after initially being misinformed of the intentions of such research, decided it was time to revisit certain files which he had decided needed not be aired until such a time was befitting, in regards actual Japanese Intelligence to substantiate or otherwise, such claims which by now had caused much debate over the internet, as since viewed by this writer.

Little will be said in regards this aspect then two points of concern 1) in the name of ADF heritage preservation and the sharing of such, the intervention of personal politics, racial bigotry, and misuse of primary resources does nothing but harm to a genre those doing such too, profess to be passionate about serving! 2) the internet as a medium or carriage of conveying and preserving actual history should be avoided, and the free range which some commercial net site’s feel they own, in this case those concerned with the Kokoda Trail have demonstrated over the last few years, especially since 2010, whereby distorting published works to be bent to their requirements, is to say the least deplorable, and shameful.

For the record as this is meant to serve, not one Kokoda Trail type orientated site, presently carrying the piece ‘What Happened to Uncle Sam?” has even bothered to either seek the compiler’s permission to upload, nor checked to see whether their ‘new’ information, now purporting to be relevant to the piece published by this writer was suitable or even slightly correct before attaching it to the uploaded aspect of ‘Mud Over Blood’ and using my name as its credibility!

To this the only site which this compiler has availed permission to use the piece regards Templeton is Wayne Wetherall from Kokoda Spirit, and this is because both his claims (in their greater degree have been proven officially), and that Wayne Wetherall, had the good manners to actually ask the compiler’s permission, and had valid information which the writer felt was indeed actually relevant and new. This is not a claim any other site carrying this the writer’s piece and connecting ‘their new research’ to can presently claim!

The new information which will be availed the Australian public in published form later this year, will carry the actual facts and missing details in regards the loss, the captivity and the audacious bravery of this fine officer on the Kokoda Trail, and it will reflect the steadfast loyalty of those other six, till now completely overlooked by historians etc, and now as well captive, carried on with, and thus stood by their officer until death.

It will explain the reasons why ‘that grave’ at the Waterfall on the Kokoda Trail at Oivi now lies empty, and it will explore the fate of the actual remains from this and for those of the other six men captured, and finally after over two weeks of captivity on the Kokoda Track were killed.

This research will as well explain the final fate and whereabouts of Lieutenant Hercules ‘Hec’ Crawford, whose disappearance has been for decades confused with the mystery of Templeton’s loss. Another of the forgotten men, lost in the mystery by academics and historians in their quest for Sam.

From the officially records of the I.J.A. and from other members of the same Regiment as Nishimura comes more compelling proof, all primary, indicating the manner in which Templeton faced his death on the Kokoda Trail, and well explains in their own words as exactly how much harm this officer had caused his enemies advance towards Port Moresby along the Kokoda Trail, in what were some of the darkest days experienced by this young Nation during what is now collectively termed ‘The Battles that Saved Australia’, and during which, these seven men were to play an extraordinary part in fighting.

The story to come, to be compiled by Carl Johnson, Wayne Wetherall & Sarah Well’s, will demonstrate that to our national shame, the deeds of Captain Templeton on the Kokoda Track in protecting his new adopted homeland, is better known and celebrated by the Japanese people then it is by the Australian public!

The first step has been taken to officially acknowledge the deeds of Sam and his men in his own country. By using the firsthand accounts and actual I.J.A. Intelligence as now available to the compilers of this pending work, the names of all seven have finally been added to the National Prisoners of War Memorial at Ballarat on 5th February 2012, a mute tribute to those thousands of Australians who paid the highest price for our Nation’s freedom.

Captain Templeton lived up to all he stood for, – in life, the 39th’s motto, ‘Factis Non Verbis’ -‘Deeds Not by Words’. And in death, the Australian P.O.W’s oath. “When you get back home tell them this, that we gave up our todays, – for their tomorrows”.

Sam and his men’s deception of their enemy under interrogations brought the 39th Battalion two valuable weeks to muster further towards the defence of the Kokoda Track, they brought too Port Moresby two weeks to better prepare herself for what could well be a bitter besiegement.

They brought these at the cost of their own lives. – ‘Lest We Forget’

Carl Johnson

Compiler

Mud over Blood and Mud over Blood Revisited

Stories from the 39thInfantry Battalion 1941-43